Developing a super-white material that cools itself during the day

As a graduate student in the

Thermal and Optics Group at Princeton University, my first research project was on developing a thin material that can cool itself during the day without any additional energy input. Known was daytime radiative cooling, this technology is in its early stages, and some recent commericalization efforts have been made by startups like

SkyCool Systems and

3M.

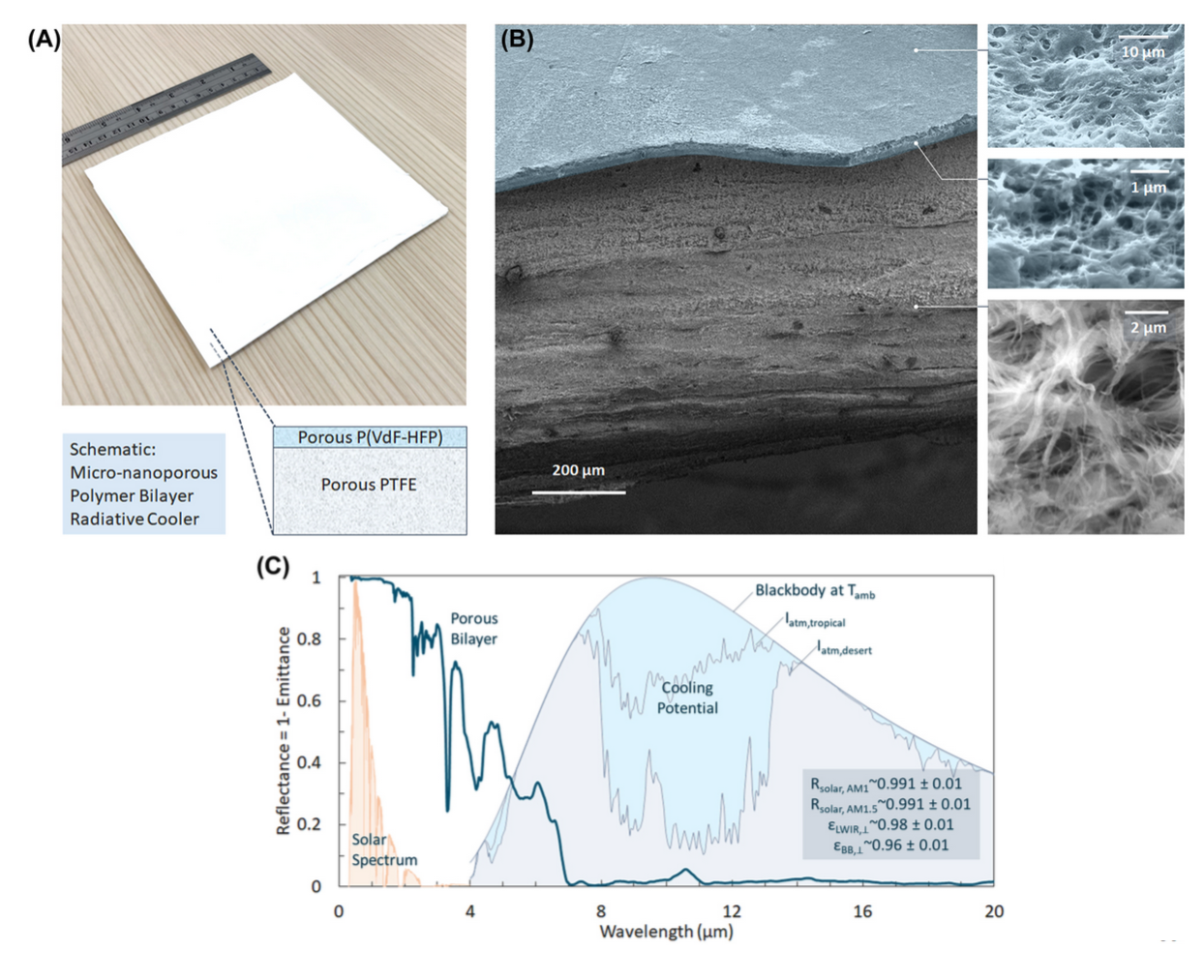

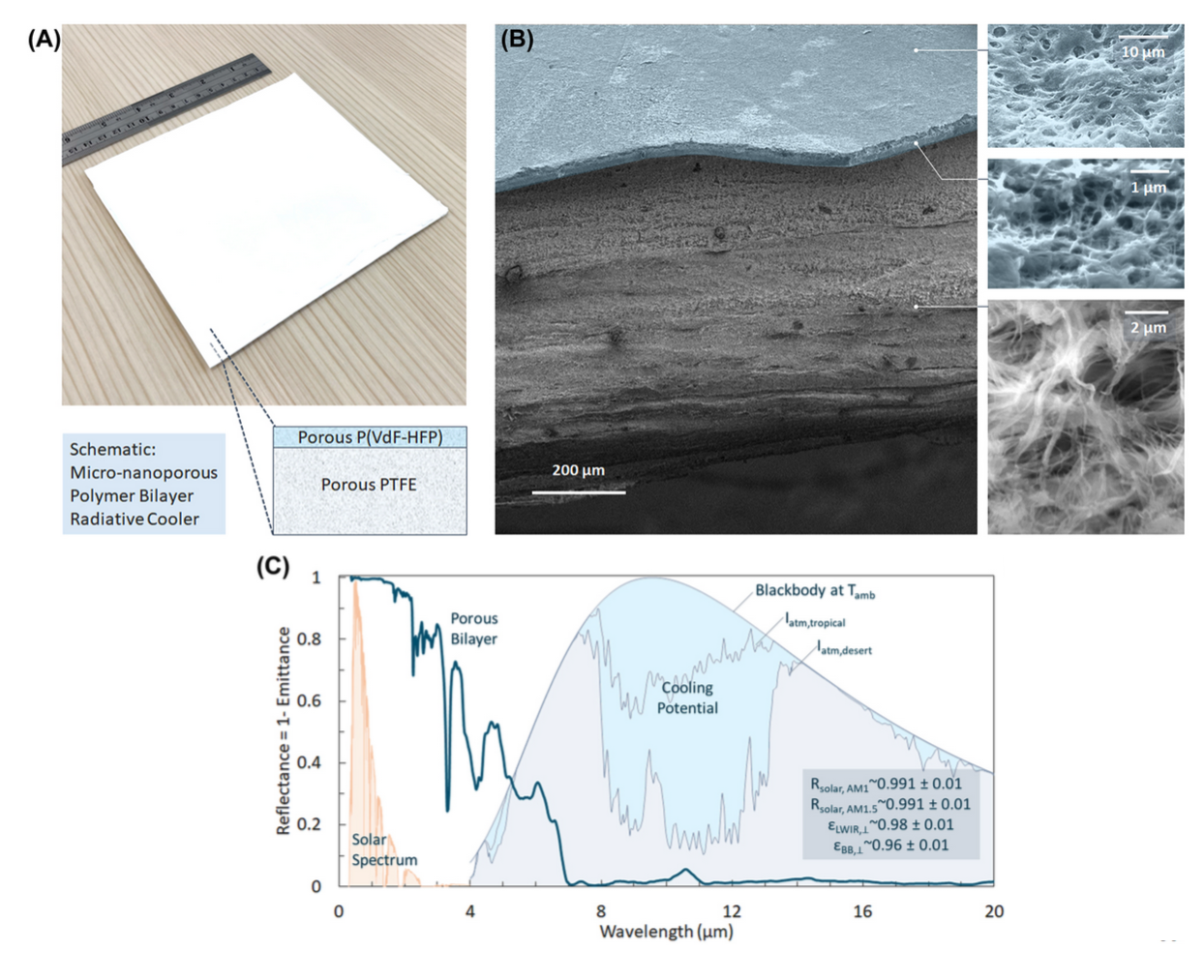

Subfigure A is a 6"x6" ePTFE-P(VdF-HFP) bilayer radiative cooler. Subfigure B are scanning electron micrographs of the bilayer with both the top surface and cross-section in view. Subfigure C is the reflectance spectrum of the radiative cooler. The background shows a normalized solar spectrum, and atmospheric irradiance showing cooling potentials for different sky conditions.

Subfigure A is a 6"x6" ePTFE-P(VdF-HFP) bilayer radiative cooler. Subfigure B are scanning electron micrographs of the bilayer with both the top surface and cross-section in view. Subfigure C is the reflectance spectrum of the radiative cooler. The background shows a normalized solar spectrum, and atmospheric irradiance showing cooling potentials for different sky conditions.

As the need for sustainable cooling solutions intensifies alongside rising energy consumption and the impacts of climate change, traditional methods fall short due to their high energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. Our study introduces a novel, scalable design for a radiative cooler that operates without external energy by dissipating heat directly into the coldness of space. Remarkably, this system remains effective even under the extreme conditions of the Saharan desert.

Daytime radiative cooling materials are an active field of academic research, and in general there are three limitations that prevented the widespread adoption of this technology: high conductive thermal resistance, scalability and stability against extreme weather. We addressed these limitations by designing a thin bilayer structure that is easily fabricated from commercially available materials typically used in extreme environments. This unique approach allows the us to achieve a high cooling power of ~50 W/m^2 under direct sunlight and humid conditions, while maintaining a largely scalable and stable design.

Optical Design Strategy

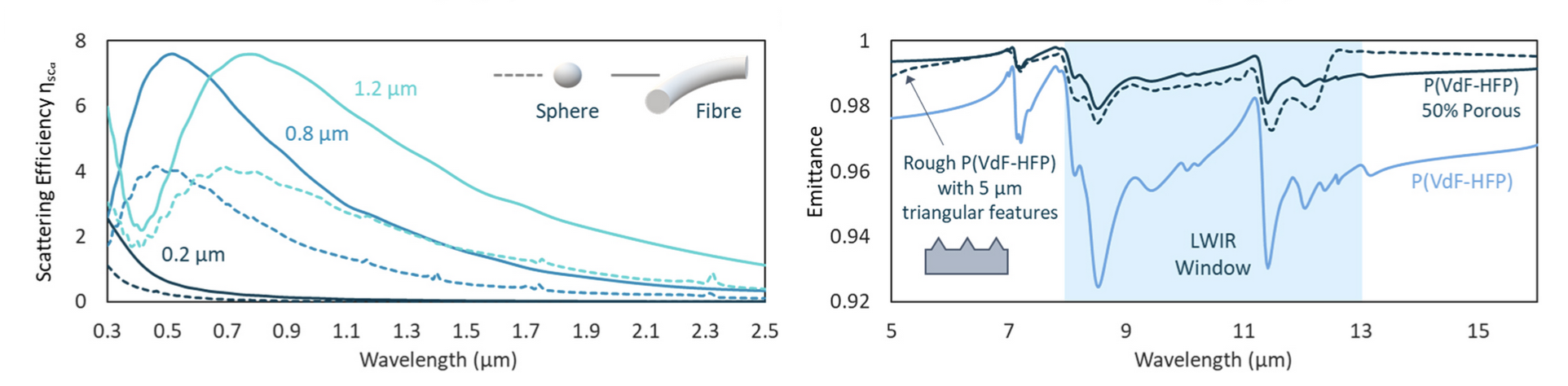

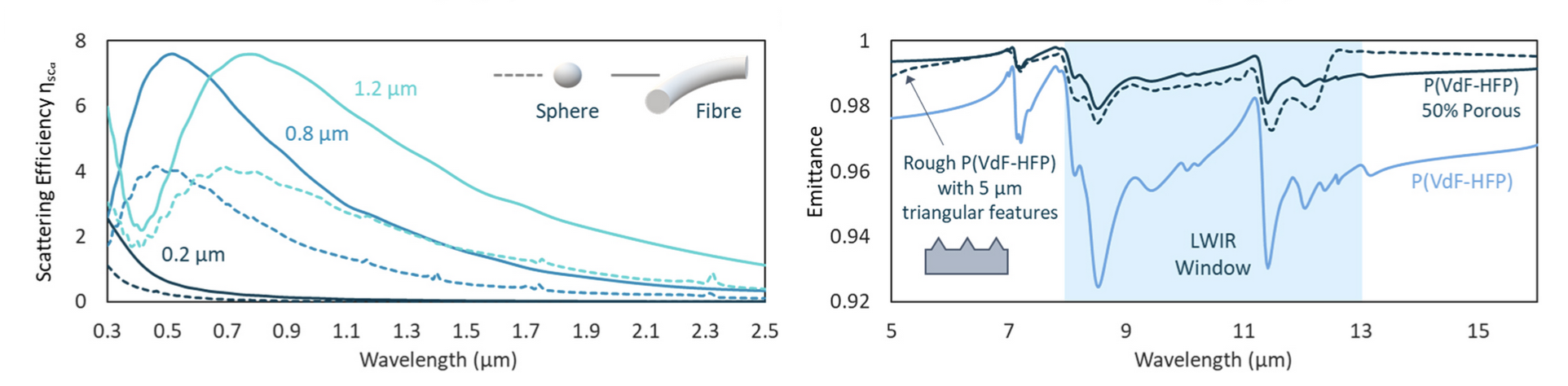

To simplify the design process, we opted to seperate the structure into two distinct layers based on spectral regimes at which they operate. In the thermal wavelengths, we aimed to achieve a high emittance by leveraging the effective emissivity of a disordered structure. By leveraging a phase inversion process developed here at Princeton, we were able to create a porous polymer with a high emittance of 0.97 in the longwave infrared. For the bottom layer where solar wavelengths are of primary importance, to achieve an optimal reflecter by leveraging mie scattering, we needed to select a suitable disordered microstucture with the correct lengthscale and geometry. We leveraged FDTD simulations to calculate the scattering cross section of a variety of disordered structures and found that a porous polymer with a 1.5um lengthscale was optimal for our application.

The subfigure on the left shows the comparison in scattering efficiency between different microgeometries, and The subfigure on the right demonstrates the increase in emittance with effective medium approximation.

The subfigure on the left shows the comparison in scattering efficiency between different microgeometries, and The subfigure on the right demonstrates the increase in emittance with effective medium approximation.

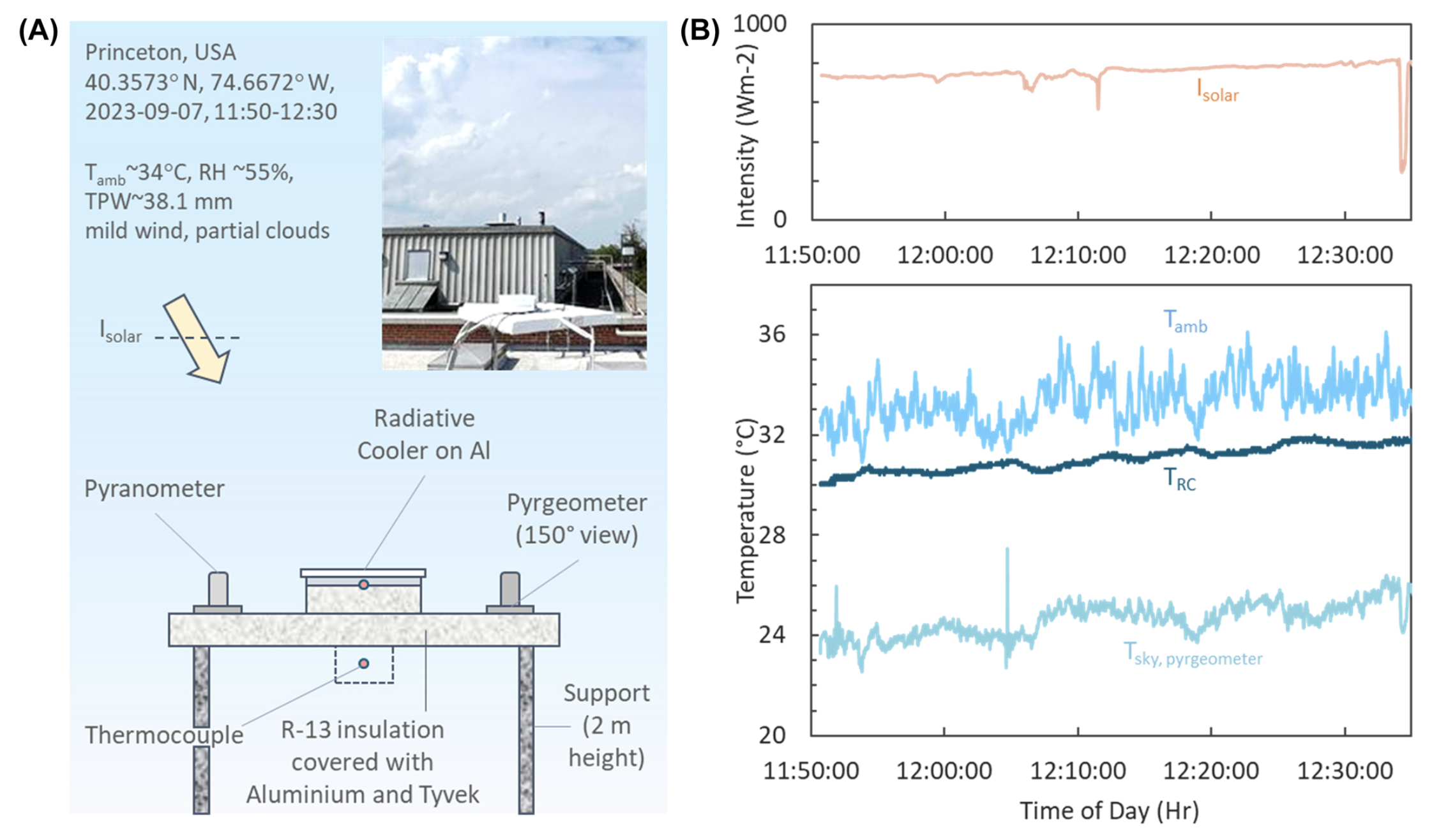

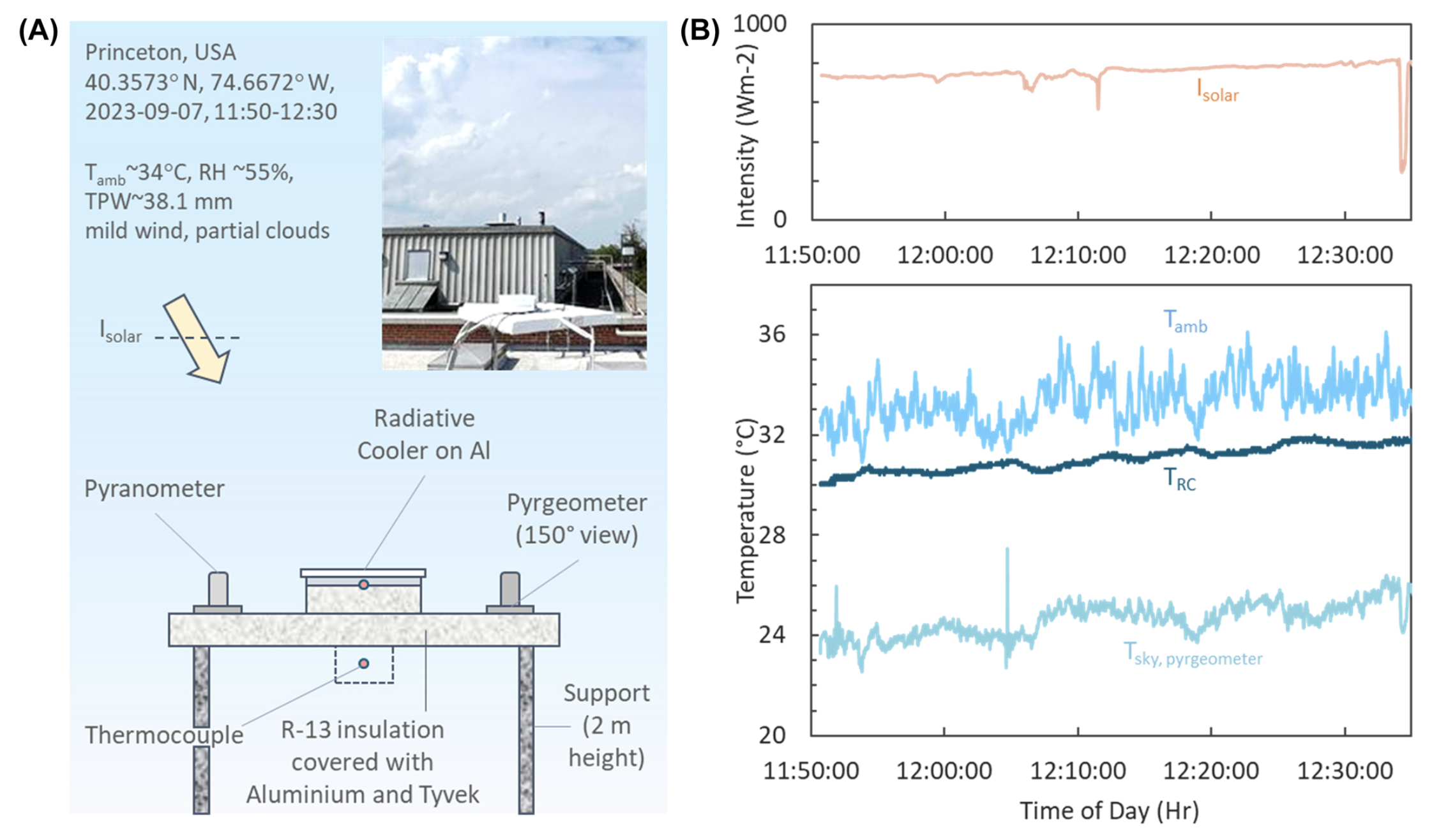

Lastly, we conducted outdoor experiments to demonstrate sub-ambient cooling performance in a rooftop setting by using a 6"x6" sample fabricated in our lab. On a hot, humid summer day at Princeton, the radiative cooler was placed on a cooling target and exposed to direct sunlight (~750 Wm^2), and we were able to measure an average of 2.26°C cooling below ambient temperature.

Experimental validation of radiative cooling performance in rooftop setting.

Experimental validation of radiative cooling performance in rooftop setting.